David Graeber has been on my radar since the start of Occupy last year. Between his involvement there and a variety of commentaries and discussions on his book Debt, I was primed to be a fan. Then he wrote an essay about superheroes. What he has to say is not very insightful. I’m honestly pretty disappointed.

It starts off badly:

Let me clarify one thing from the start: Christopher Nolan’s Batman: The Dark Knight Rises really is a piece of anti-Occupy propaganda.

Graeber asserts this, of course, despite Nolan’s explicit claims to the contrary. Okay, let’s come back to Nolan and DKR in a minute. Graeber also has some ideas about the superhero genre in general. These are equally bad:

Superman is a Depression-era displaced Iowa farm boy…

As Keith Brown pointed out in a Facebook conversation, it is hard to take someone trying to talk about superheroes seriously when they make a pretty basic mistake about the most iconic character in the genre. You know, the one from Kansas.

The superhero genre is, Graeber says, “essentially Freudian.” They are stories where the Id is played out by the villains, the only creative figures in any superhero story, who are then clubbed into submission by the super-powered embodiment of the superego. The plot is circular, ending with a complete return to the status quo. This simplification, of course, is entirely untenable to anyone familiar with the more complex 1940’s superheroes, much less the pinnacles of the genre. Which is not to say that there aren’t stories that fit Graeber’s stereotype, even a large number of them; but it does violence to the genre to treat such stories as essential.

The main point that Graeber wants to make about superhero comics is political. Superhero comics by and large have “extremely conservative political implications,” according to Graeber, and this goes some way to explaining what went wrong with Nolan’s DKR. To his credit, Graeber doesn’t say anything so simplistic as baldly stating that superheroes are fascists. Indeed, he appears to say the opposite:

They aren’t fascists. They are just ordinary, decent, super-powerful people who inhabit a world in which fascism is the only political possibility.

There’s a lot to unpack there, and a lot of it comes from some basically implausible general claims about the legitimacy and authority of law. As an aside, this discussion (in section IV) is remarkably weak. I haven’t spent a lot of time reading Graeber, but what I had read before led me to expect better than this. This stuff would not really pass muster in an undergraduate political philosophy / theory course. It’s disappointing to hear that this is how one of the premier theorists of anarchism thinks about these things.

The problem of fascism comes from the repetitive, circular drama of the superhero genre. They teach us (meaning the “adolescent or pre-adolescent white boys” who read superhero comics) that “imagination and rebellion lead to violence” and that “These things must be contained!” And so:

It’s in this sense that the logic of the superhero plot is profoundly, deeply conservative. Ultimately, the division between Left- and Right-wing sensibilities turns on one’s attitude towards the imagination. For the Left, imagination, creativity, by extension production, the power to bring new things and new social arrangements into being, is always to be celebrated. It is the source of all real value in the world. For the Right, it is dangerous, and ultimately evil. The urge to create is also a destructive urge. This kind of sensibility was rife in the popular Freudianism of the day: the Id was the motor of the psyche, but also amoral; if really unleashed, it would lead to an orgy of destruction. This is also what separates conservatives from fascists. Both agree that the imagination unleashed can only lead to violence and destruction. Conservatives wish to defend us against that possibility. Fascists wish to unleash it anyway. They aspire to be, as Hitler imagined himself, great artists painting with the minds, blood, and sinews of humanity.

So superheroes have the distinction of being reactionary and conservative rather than fascist, because these are the only options, and superheroes are basically decent.

I mean, look, there are obviously some disturbingly reactionary and fascistic strains in the superhero genre. We all know it, and Alan Moore, Warren Ellis, and others have played with this fact in fascinating ways. But what Graeber is telling us is all very superficial. It is based on a superficial and ultimately false characterization of the superhero story as Freudian, repetitive, cyclical, uncreative, etc. I look at Marston’s Wonder Woman, the insane worlds of Fletcher Hanks, Jack Kirby’s New Gods, the politically engaged works of Denny O’Neil, the height of the X-Men comics, and the best Batman tales, and I see something very different. I see characters with projects, wrestling with a universe that is a close reflection of the times the books were written, adapting to new circumstances. I see mythical tales playing out some of the most central human concerns.

If we restrict ourselves to what he says about the Nolan Batman movies, which he seems to have actually watched carefully (unlike the comics, where he appears to have read a few Wikipedia articles), he has somewhat better points to make. But ultimately, I think reading DKR as a response to Occupy is silly, and Graeber’s counter-punch to the perceived slight comes across as shrill and hypersensitive. Obviously some references were thrown in by Nolan to create some superficial resonances to current politics, including Occupy. Graeber is reading way too much into that.

Graeber doesn’t understand what Batman is about, and so he doesn’t understand what the Nolan movies are about, and so he reads DKR all wrong. There is something deeply Freudian about Batman, but not what Graeber thinks. There are disturbing reactionary moments in the movies and Batman in general, but not where Graeber thinks they are. Batman’s motivations are essentially the motivations of a scarred child, who in, a moment of trauma, reifies and personifies a simple, desperate criminal act into Crime itself, and pledges to fight Crime until it is destroyed. The very idea is bizarre and perhaps incoherent, but it is the driving idea behind Batman. There is certainly something reactionary, even fascistic, about an extremely wealthy man dedicating his life to beating the pulp out of the desperate, downtrodden people who resort to crime, the working-class cops in a corrupt town who give in to corruption in order to survive, to the criminally insane. But Batman isn’t really out to persecute these people. He’s not waging war against the criminals, he’s waging war against Crime, an impossible, incoherent war that perfectly fits the superhero genre’s position in our culture, that of creating a contemporary mythology.

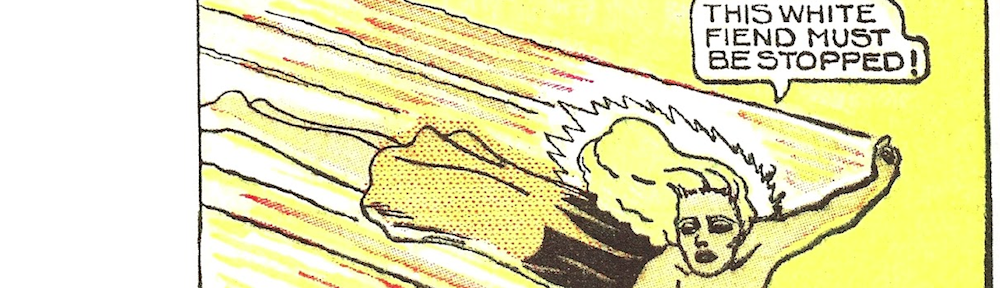

Cover image by the one and only Fletcher Hanks, from Fantomah, Mystery Woman of the Jungle

Your last paragraph confirms the point Graeber makes. In the world of superheroes the only way to fight crime is “beating the pulp” out of them. Why not read some economic studies and figure out that creating employment opportunities is much more efficient. And guess what, Mr. Wayne is exactly in a position to do a lot in that regard. Instead he opts out to get himself fancy suit with rubber ears, construct cave, build cars, motorcycles and even flying vehicles. All those funds could have employed thousands of potential joker/bane sidekicks for years.

This criticism is only a serious one if we are taking the Bat-Man literally – What would we say about a real Batman? But that is… kind of a crazy ground for criticism? Whether superheroes are adolescent fantasies or mythic figures or characters in literary narratives, surely it is not a very good critique to say, that would not be the most efficient, effective, or ethical way for a REAL Bruce Wayne to fight crime. That’s missing the point.

“This criticism is only a serious one if we are taking the Bat-Man literally” Or Iron Man, the fantastic four, SHIELD, the X-Men, Wonder Woman and Thor are essentially Gods. Of course arguing about what a real Batman would do is important, how else do you judge the actions of any fictional character, fantasy, science fiction, soap opera, by judging them off the back of their own morals, people wouldn’t stand for a Batman who raped children or who could fly, because the first would appall our morals and the latter our logic.

I take your point. I’m not suggesting that there is no room for moral evaluation of superhero comics or the characters therein. Still, it seems to me a mistake to reduce the analysis of Batman and Batman comics (much less the entire genre) to the analysis of what we would think about characters, IF they were actual people in the actual world. Again, that misses the point of the work. Batman comics are not presenting a recommendation for what the super-wealthy should do to combat the problems of society.